|

|

|

|

|

The Bolshoi Theatre began its life as the private theatre of the Moscow proseсutor Prince Pyotr Urusov. On 28 March 1776, Empress Catherine II signed and granted the Prince the 'privilege' of organizing theatre performances, masquerades, balls and other forms of entertainment for a period of ten years. It is from this date that Moscow's Bolshoi Theatre traces its history.

At first, the Bolshoi Theatre's Opera and Dramatic Troupes formed a single company. Company members came from very diverse backgrounds – all the way from serf artists to guest stars from abroad.

Moscow University and its gymnasium, both of which provided a good musical education, played a major role in the formation of the Opera and Drama Company. Theatre classes were organized at the Moscow Foundling Home which was also a source of recruits for the new Company.

The organization of theatre performances and 'entertainments' involved a heavy financial burden and Prince Pyotr Urusov shared his 'privilege' with a business partner, the Russophile Englishman and theatrical entrepreneur Michael Maddox. The latter was also an equilibrist, theatre mechanic and 'lecturer', who demonstrated various types of optical equipment and other 'mechanical' marvels.

The Theatre's first building was erected on the right bank of the River Neglinka. It stood on Petrovka Street, whence the Theatre derived its name Petrovsky (it was subsequently to be called the Old Petrovsky Theatre). The Theatre opened on 30 December 1780. The opening performance consisted of a solemn prologue The Wanderers written by Alexander Ablesimov and a big pantomime ballet The Magic School, produced by Leopold Paradis to music by Joseph Starzer. Later on the Theatre repertoire consisted for the most part of Russian and Italian comic operas with ballet interludes, and separate ballets.

The Petrovsky Theatre, which was built in record quick time – less than six months, was the first public Theatre building of such size and beauty to be erected in Moscow. True, by the time the Theatre opened, Prince Urusov had already ceded his rights to his business partner and, in the future, the 'privilege' was renewed in the name of Maddox alone.

However, the latter's expectations too were dashed. Constantly forced to request loans of the Government Loan Office (Board of Trustees), Maddox was steeped in debt. Added to which, the authorities' opinion – which to begin with had been very positive - of the quality of his entrepreneurial activities underwent radical change. In 1796, the lease of Maddox’s personal 'privilege' ran out and so both Theatre and its debts were transferred to the Government Loan Office.

In 1802-03 the Theatre was farmed out to Prince M. Volkonsky, who owned one of Moscow's best private theatre companies. But in 1804, when the Theatre was transferred back to the Government Loan Office, Volkonsky was in effect appointed its salaried director.

In 1805 it was decided to set up a theatre directorate in Moscow "along the lines" of the Directorate of Imperial Theatres in Petersburg. And in 1806 this project was realized and the Moscow Theatre acquired the status of imperial, coming under the joint Directorate of Imperial Theatres.

In 1806 the Petrovsky Theatre School was reorganized into the Moscow Imperial Theatre College for the training of opera, ballet and theatre artists and theatre orchestra musicians (in 1911, it became the Moscow School of Ballet).

In the autumn of 1805, the Petrovsky Theatre building burnt down. The Company began to appear with different private theatres and from 1808 at the new Arbat Theatre, designed by Carlo Rossi. During the 1812 war against Napoleon this wooden building also went up in flames.

In 1819 a competition for designs for a new theatre was announced. It was won by Andrei Mikhailov, a professor at the Academy of Arts. His design, however, was declared to be too expensive. Therefore, the Governor of Moscow Dmitry Golitsyn commissioned architect Joseph Bové to alter it, which the latter did, considerably improving it in the process.

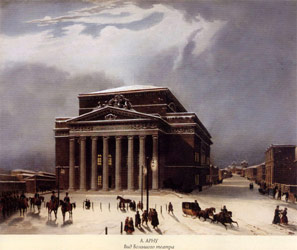

In July 1820 work started on building the new theatre which was to become the central feature in the architectural composition of the projected (Theatre) square to be laid out in front of it and adjacent streets. The facade, decorated by a massive eight columned portico surmounted by a pediment on which stood a large sculptural group – Apollo in a chariot drawn by three horses, 'surveyed' Theatre Square which was under construction, greatly adding to the latter's beauty.

In 1822-23 the Moscow theatres were removed from the joint Directorate of Imperial Theatres and handed over to the Moscow Governor General who was given the power to appoint the directors of the Moscow imperial theatres.

"Even closer, standing on a broad square, is the Petrovsky Theatre, a pioneering piece of architecture, a huge building, built with great taste, with a flat roof and imposing portico, surmounting which is an alabaster Apollo, standing motionless on one leg in an alabaster chariot, and driving three alabaster horses while gazing with annoyance at the Kremlin wall which jealously cuts him off from Russia’s ancient and sacred monuments!"

Mikhail Lermontov, in a work he wrote as a young man A Panorama of Moscow

On 6 January 1825 the solemn opening ceremony for the new Petrovsky Theatre took place – as it was much bigger than its predecessor it was known as the Big (Bolshoi) Petrovsky Theatre. A prologue in verse (M. Dmitriev) specially written for the occasion was performed The Triumph of the Muses, with choruses and dances to music by Alexander Alyabiev, Alexei Verstovsky and F. Scholtz, and also a ballet Cendrillon produced by a guest ballerina and ballet-master from France Félicité Hullen-Sor, to music by the latter’s husband, Fernando Sor. Muses triumphed over the blaze which destroyed the old theatre building and, led by the Genius of Russia, a role danced by the twenty-five-year-old Pavel Mochalov, raised from the ashes a new temple to art. And though the Theatre was indeed very large, it was unable to accommodate all those who wished to be present. In recognition of the importance of the moment and as a conciliatory gesture towards those who had failed to gain admittance, the production was repeated in full the next day.

The new Theatre, which was bigger even than Petersburg's Big (Bolshoi) Stone Theatre was distinguished by its monumental grandeur, its perfect proportions, the harmony of its architectural forms and the richness of its interior decoration. It was very comfortable: there were galleries where the public could promenade, staircases leading to the tiers, corner and side rooms for the audience to rest in and capacious cloakrooms. The huge auditorium could accommodate over two thousand people. The orchestra pit was deepened. During masquerades the stalls' floor was raised to the level of the forestage, the orchestra pit being covered over by special panels and - the end result was an excellent dance floor.

In 1842 the Moscow theatres were again subordinated to the joint Directorate of Imperial Theatres. The director at the time was A. Gedeonov, while the famous composer Alexei Verstovsky was appointed manager of the Moscow Theatre office. The years he was 'in command' (1842-59), were known as the "Verstovsky age".

Though the Bolshoi Petrovsky Theatre continued to present dramatic productions, more and more of its repertoire was given over to opera and ballet. It produced works by Donizetti, Rossini, Meyerbeer, the young Verdi and of the Russian composers – works by both Verstovsky and Glinka (in 1842 the Moscow première of A Life for the Tsar took place and in 1846 – of the opera Ruslan and Lyudmila).

The building of the Bolshoi Petrovsky Theatre stood for almost 30 years. But it too was overtaken by the same sad fate: on 11 March 1853 a fire broke out in the Theatre and continued for three days, burning everything which came in its path – theatre machines, costumes, musical instruments, notes, sets… The building itself was virtually totally destroyed, all that remained of it were the charred stone walls and portico columns.

Three leading Russian architects participated in the competition for the rebuilding of the Theatre. The competition was won by Alberto Cavos, chief architect of the imperial theatres and a professor of the Petersburg Academy of the Arts. Cavos, who specialized in building theatres, had an excellent grasp of theatre technology and of designing multi-tiered theatres with box-stage and Italian and French-type boxes.

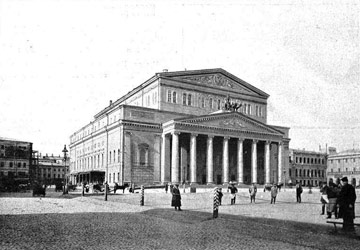

Restoration work progressed at a rapid pace. In May 1855 the demolition and clearing away of the ruins was completed and the reconstruction of the building began. In August 1856 the Theatre opened its doors to the public. That the building was completed with such speed is explained by the fact that it had to be ready in time for the coronation celebrations of Emperor Alexander II. The Bolshoi Theatre which was virtually built anew and with major modifications by comparison to the previous building, opened on 20 August 1856 with a performance of Vincenzo Bellini's opera I Puritani.

The overall height of the building increased by almost four metres. Despite the fact that Bové's portico with columns remained, the appearance of the main facade underwent fundamental change. A second pediment appeared. Apollo's troika-led chariot was replaced by a quadriga cast in bronze. The inner field of the pediment was decorated with an alabaster bas -relief consisting of winged geniuses with lyre. The frieze and capitals of the columns were altered. Sloping roofs on cast iron pillars were erected over the theatres' side facade entrances.

But it was on the auditorium and stage and backstage areas that Cavos, of course, concentrated his attention. In the second half of the 19th century the Bolshoi was considered to be one of the best theatres in the world in terms of its acoustic qualities. A reputation it owed to the skill of Alberto Cavos who designed the auditorium as a huge musical instrument. The auditorium walls were lined with acoustically resonant pinewood panels, the iron ceiling was replaced by a wooden one, the painted plafond being constructed out of wooden panels – everything in the auditorium – even the decoration of the boxes made out of papier-mâché - was geared to the acoustics. To improve the acoustics, Cavos also filled in the space, occupied by a cloakroom, under the amphitheatre, the former being moved to the stalls' level.

There was a considerable increase in the space occupied by the auditorium which made it possible to provide the boxes with anterooms – small drawing-rooms done up to entertain visitors from the stalls or from neighboring boxes. The six-tier auditorium accommodated almost 2300 people. The lettered boxes closest to the stage on both sides of the auditorium were reserved for the Tsar's family, court ministries and Theatre management. The Tsar's box, opposite the stage and protruding a little into the auditorium became the latter's central feature. The bottom of the Tsar's box was supported by consoles in the form of bent Atlantes. The crimson-gold magnificence of the auditorium impressed all those who entered it – both in the first years of the Bolshoi Theatre's existence and in later decades.

"I tried to decorate the auditorium as extravagantly but at the same time as lightly as possible, in Renaissance taste mixed with Byzantine style. The white light, interspersed with gold, the bright crimson draping of the interiors of the boxes, the stucco arabesques, different for each floor and the main eye-catcher of the auditorium – the huge chandelier consisting of three tiers of lights and candelabras decorated with crystal – all this has aroused universal approval".

Alberto Cavos

The auditorium chandelier was originally lit by 300 oil lamps. In order to light the oil lamp wicks, the chandelier had to be hoisted through an opening in the plafond into a special chamber. It was this opening that dictated the circular composition of the Apollo and the Muses plafond painted round it by Academician Alexei Titov. There is a secret attached to this mural which will be noticed only by the most observant of spectators who, in addition, has to be a connoisseur of ancient Greek mythology: in place of one of the canonic muses – Polyhymnia, the Muse of the sacred hymn, Titov has depicted a muse of his own invention – the Muse of painting – with palette and brush in hand.

The main house fly curtain was created by the Italian artist Cosroe Dusi, a professor of the Petersburg Imperial Academy of Fine Arts. Its theme Minin and Pozharsky's entrance into Moscow was selected from a choice of three sketches. In 1896 it was replaced by a new curtain View of Moscow from Sparrow Hills (made by Pyotr Lambin from a drawing by Mikhail Bocharov), used at the beginnings and ends of performances. And for the intervals one more curtain was made –The Triumph of the Muses from a sketch by Pyotr Lambin (today the only remaining 19th century curtain in the Theatre's possession).

After the 1917 Revolution, the imperial theatre curtains were 'banished'. In 1920, in the course of working on a production of Lohengrin theatre artist Fyodor Fyodorovsky designed a bronze-coloured canvas draw curtain, which would later be used as the main curtain. In 1935 a new curtain was made based on a sketch by Fyodor Fyodorovsky on which were weaved the revolutionary dates – "1871, 1905, 1917". From 1955, for fifty years, Fyodor Fydorovsky's famous gold 'Soviet' curtain, bearing the state symbols of the USSR, reigned supreme at the Theatre.

As with the majority of the buildings in Theatre Square, the Bolshoi Theatre was built on piles. Gradually the building decayed. Drainage work lowered the level of subsoil waters. The upper part of the piles rotted, and this resulted in major subsidence to the building. Repairs to the foundations were carried out in 1895 and 1898 which, for a time, put a stop to the ongoing destruction.

The last performance at the Imperial Bolshoi Theatre took place on 28 February 1917. And on 13 March the State Bolshoi Theatre opened its doors to the public.

Following the October Revolution, not only its foundations, the Theatre's very existence came under threat. Several years were to pass before the authorities, in the shape of the victorious proletariat, were to give up for good their idea of shutting down the Bolshoi Theatre. In 1919 the title of Academic was bestowed on the Theatre which in those times was no guarantee of safety for, within a few days, the issue of whether or not to close it down was again being hotly debated.

However, in 1922, the Bolshevik government decided that to close the Theatre was not economically feasible. By this time, it had already 'adapted' the building to its own needs with a vengeance. The All-Russian Congresses of Soviets, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee sessions, the Comitern Congresses – were all taking place at the Bolshoi Theatre. And it was from the Bolshoi Theatre stage that the formation of a new country – the USSR – was proclaimed.

In 1921 a special government commission, examining the Theatre building, found its condition to be catastrophic. It was decided to undertake emergency repairs under the direction of architect Ivan Rerberg. It was at this time that the foundations under the semi-circular auditorium walls were reinforced, the cloakrooms overhauled, the staircases replanned, new rehearsal rooms and dressing-rooms created. In 1938 a major reconstruction of the stage was carried out.

The General Reconstruction plan for Moscow (1940-41) envisaged the demolition of all buildings between the Bolshoi Theatre and Kuznetsky Most Street. And on the resulting empty space it was planned to put up the auxiliary buildings the Theatre so badly needed. As for the Theatre itself, it was to be equipped with fire-safety and ventilation systems. In April 1941, the Bolshoi Theatre closed for renovation. Just two months later the Germans invaded the USSR.

Part of the Bolshoi Theatre Company went into evacuation in Kuibyshev, part remained in Moscow and continued to give performances at the Bolshoi Filial, its 2nd stage. Many artists went to the front to entertain the troops, while others joined up and went off to defend their country.

At 4 p.m., on 22 October 1941, a bomb fell on the Bolshoi Theatre building. The shock wave passed obliquely between the portico columns, went through the facade wall and did considerable damage to the Lobby. Despite the wartime hardship and the severe cold, restoration work on the Theatre was initiated in winter 1942.

And by autumn 1943, the Bolshoi Theatre had again opened its doors to the public with a production of Glinka's opera A Life for the Tsar from which the monarchical stigma had been erased and its patriotic and popular appeal acknowledged though, true, in order to achieve this, the libretto had to be revised and the opera given a new politically correct title – Ivan Susanin.

Cosmetic repairs were done on a yearly basis at the Theatre. And larger scale renovation work was regularly undertaken. But, as before, rehearsal space was woefully inadequate.

In 1960 a big rehearsal room, right under the roof, was equipped and opened at the Theatre in a room which had previously served as a stage decorations workshop.

In 1975 some restoration work in the auditorium and Beethoven Hall was carried out for the Theatre's 200th anniversary. The main problems, however – the instable foundations and lack of space within the Theatre – had not been solved.

Finally, in 1987, came a government decree in which the decision was taken to undertake urgent reconstruction work at the Bolshoi Theatre. It was clear to everyone, however that, in the interests of keeping the Company together, it simply had to go on working. What was wanted was a second stage. Eight years were to go by before the cornerstone was set in the foundations of the Bolshoi's New Stage. And another seven before building work on it was completed.

29 November 2002. The New Stage opened with the première of a new production of Rimsky-Korsakov's The Snow Maiden, a production which was fully in keeping with the new building's spirit and designation, i.e., it was innovational and experimental.

In 2005 the Bolshoi Theatre Historic Stage shut for reconstruction and refurbishment. But this is a separate chapter in Bolshoi Theatre history.

(to be continued)

Print page