Biography

George Balanchine, who is regarded as the foremost contemporary choreographer in the world of ballet, came to the United States in late 1933 following an early career throughout Europe.His trip to the United States in 1933 was at the invitation of Lincoln Kirstein, the Boston born dance connoisseur whose dream it was to establish an American school of ballet equivalent to the European schools, as well as an American ballet company. Kirstein had met Balanchine in Paris after seeing a performance by the company that Balanchine was then directing there, Les Ballets 1933; the two were introduced by Romola Nijinsky, widow of the famous Russian dancer, whom Kirstein assisted in her research for a biography of her late husband.

The first result of the Balanchine Kirstein collaboration was The School of American Ballet, founded in early 1934 (the first day of class, in fact, was January 1 of that year) and existing to the present day. It later became the training ground for dancers going into New York City Ballet, which Balanchine and Kirstein were to establish together after 14 more years, in 1948. Balanchine’s first ballet in this country was Serenade, choreographed in 1934 to music by Tchaikovsky, which was premiered outdoors on the estate of a friend near White Plains, New York, as a workshop performance.

In 1935, Kirstein and Balanchine set up a touring company of dancers from the school and called it the American Ballet. That same year the Metropolitan Opera invited the company to become its resident ballet, with Balanchine as the Met’s ballet master. Tight funding, however, permitted Balanchine to mount only two completely dance-oriented works while with the Met, a dance drama version of Gluck’s Orfeo and Eurydice and an all-Stravinsky program, featuring a revival of one of Balanchine’s first ballets, Apollo, plus two new works, Le Baiser de la Fée, and Card Game.

Despite the popular and critical success of the latter program, Balanchine and the Met parted company in early 1938, and Balanchine spent his next few years teaching at the School and working in musical theatre and films. In 1941, he and Kirstein assembled the American Ballet Caravan, sponsored by Nelson Rockefeller, which toured South America with such new Balanchine creations as Concerto Barocco and Ballet Imperial (later renamed Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2). Then from 1944 to 1946, Balanchine was called in as artistic director to help revitalize the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo; he created Raymonda and La Sonnambula for them.

In 1946 Balanchine and Kirstein collaborated again to form Ballet Society, a company which introduced New York subscription only audiences over the next two years to such new Balanchine works as The Four Temperaments (1946) and Stravinsky’s Renard (1947) and Orpheus (1948).

On October 11, 1948, Morton Baum, chairman of the City Center finance committee, saw Ballet Society in a City Center Theater program that included Orpheus, Serenade, and Symphony in C (a ballet which Balanchine had created for the Paris Opera Ballet under the title Le Palais de Crystal the previous year). Baum was so highly impressed that he initiated negotiations that led to the company’s being invited to join the City Center municipal complex (which at that time the New York City Drama Company and the New York City Opera were a part of) as the “New York City Ballet.” Balanchine’s talents at last had found a permanent home.

Since that time, Balanchine served as artistic director for New York City Ballet, choreographing (either wholly or in part) the majority of the now 175 productions the company has introduced since its inception. Among the most noteworthy were The Firebird (1949; restaged with Jerome Robbins, 1970); Bourrée Fantasque (1949); La Valse (1951); The Nutcracker (his first full length work for the company), Ivesiana and Western Symphony (1954); Allegro Brillante (1956); Agon (1957); Seven Deadly Sins (a revival of the original Les Ballets 1933 production) and Stars and Stripes (1958); Episodes (1959); Monumentum Pro Gesualdo and Liebeslieder Walzer (1960); A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1962); Movements for Piano and Orchestra and Bugaku (1963); Don Quixote (in three acts) and Harlequinade (in two acts) (1965); Jewels (1967) (his first full length plotless ballet) and Who Cares? (1970). In June 1972, he choreographed Stravinsky Violin Concerto, Duo Concertant, Choral Variations on Bach’s Von Himmel Hoch, Scherzo à la Russe, Symphony in Three Movements, Divertimento from Le Baiser de la Fée, and new versions of Pulcinella (with Robbins) and Danses Concertantes for the New York City Ballet Stravinsky Festival.

The son of a composer, Balanchine early in life gained a knowledge of music that far exceeded that of most of his fellow choreographers. He began studying the piano at the age of five and following his graduation in 1921, from the Imperial Ballet School (the St. Petersburg academy where he had started his dance studies at the age of nine), he enrolled in the state’s Conservatory of Music, where he studied piano and musical theory, including composition, harmony and counterpoint, for three years. Such extensive musical training made it possible for Balanchine as a choreographer to communicate with a composer of such stature as Igor Stravinsky; the training also gave Balanchine the ability to reduce orchestral scores on the piano, an invaluable aid in translating music into dance.

Balanchine made his own dancing debut at the age of ten as a Cupid in the Maryinsky Theatre Ballet Company’s production of The Sleeping Beauty. He joined the company as a member of the corps de ballet at 17 and staged one work for them, called Enigmas. Most of his energies during this period, however, were concentrated on choreographic experiments outside the company.

In the summer of 1924, Balanchine was one of the four dancers who left the newly formed Soviet Union for a tour of Western Europe. The others were Tamara Geva, Alexandra Danilova, and Nicholas Efimov, all of whom later became well known dancers in Europe and the United States. All four dancers were invited by impresario Serge Diaghilev to audition for his Ballets Russes in Paris and were accepted into the company.

Diaghilev also had his eye on Balanchine as a choreographer as well, and after watching him stage a new version of the company’s Stravinsky ballet, Le Rossignol, Diaghilev hired him as ballet master to replace Bronislava Nijinska. Shortly after this, Balanchine suffered a knee injury which limited his dancing and correspondingly bolstered his commitment to full time choreography.

Balanchine served as ballet master with Ballets Russes until the company was dissolved following the death of Diaghilev in 1929. After that, he spent the next few years on a variety of projects which took him all over Europe: choreographing for the Royal Danish Ballet; making a movie with former Diaghilev ballerina Lydia Lopoukhova (then the wife of British economist John Maynard Keynes) in England; staging dance extravaganzas for Britain’s popular Cochran Musical Theatre Revues; and working with DeBasil’s Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo (where he discovered the young Tamara Toumanova).

Returning to Paris, Balanchine formed his own company, Les Ballets 1933, collaborating with such leading artistic figures as Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill (Seven Deadly Sins), the artist Pavel Tchelitchev, and composers Darius Milhaud and Henri Sauguet. It was during this period that the meeting with Lincoln Kirstein occured, which was to lead to Balanchine’s move from Europe to the United States.

Balanchine has choreographed numerous musical comedies over the years, including On Your Toes (of which Slaughter on Tenth Avenue, a work in New York City Ballet’s repertory, was a part), Cabin in the Sky, Babes in Arms, Where’s Charley?, Song of Norway, The Merry Widow, and The Ziegfield Follies of 1935. His film credits include Star Spangled Rhythm, I Was An Adventuress, and Goldwyn Follies. He choreographed the operas The Rake’s Progress and The Magic Flute for the Met and he collaborated with Stravinsky on the television ballet, Noah and the Flood, in 1962.

Balanchine’s style has been described as neoclassic, a reaction to the Romantic anticlassicism (which had turned into exaggerated theatricality) that was the prevailing style in Russian and European ballet when he had begun to dance. As a choreographer, Balanchine has generally tended to de-emphasize plot in his ballets, preferring to let “dance be the star of the show,” as he once told an interviewer.

He always preferred to call himself a craftsman rather than a creator, comparing himself to a cook or a cabinetmaker (two crafts in which he was rather skilled). He was known throughout the dance world for the calm and collected way in which he works with his dancers and colleagues.

Balanchine himself has written: “We must first realize that dancing is an absolutely independent art, not merely a secondary accompanying one. I believe that it is one of the great arts. The important thing in ballet is the movement itself, as it is sound which is important in a symphony. A ballet may contain a story, but the visual spectacle, not the story, is the essential element. The music of great musicians, it can be enjoyed and understood without any verbal introduction and the choreographer and the dancer must remember that they reach the audience through the eye and the audience, in its turn, must train itself to see what is performed upon the stage. It is the illusion created which convinces the audience, much as it is with the work of a magician. If the illusion fails, the ballet fails, no matter how well a program note tells the audience that it has succeeded.”

Balanchine’s long time friend and collaborator, Igor Stravinsky, once described their association on one particular ballet as follows: “Balustrade, the ballet that George Balanchine and Pavel Tchelitchev made of the Violin Concerto, was one of the most satisfactory visualizations of any of my works. Balanchine composed the choreography as he listened to my recording, and I could actually observe him conceiving gesture, movement, combination, and composition. The result was a series of dialogues perfectly complimentary to and coordinated with the dialogues of the music. Hofmannsthal once said to Strauss: ‘Ballet is perhaps the only form of art which permits real intimate collaboration between two people gifted with visual imagination.’”

Architect of, and principal choreographer for, the New York City Ballet’s Homage àagrave; Ravel festival, Balanchine brought to life a three week celebration of 16 new ballets of which eight were his own creations. At a ceremony held on the evening of the Company’s Ravel Festival Gala at the New York State Theater in May 1975, the French Government proclaimed him a member of the Legion of Honor. In an extraordinary gesture of esteem, Balanchine was awarded the rank of Officer, a position usually reserved for those with many years of prior membership in the Legion.

Also in the spring of 1975, the Entertainment Hall of Fame in Hollywood inducted Balanchine as a member in a nationally televised special, hosted by Gene Kelly. The first choreographer so honored, he joins the ranks of such show business luminaries as Fred Astaire, Walt Disney and Bob Hope. Additionally, in May 1975, the National Institute of Arts and Letters presented him with a rarely given award for Distinguished Service to the Arts, an honor of special significance from the 250 leading American artists who comprise the Institute.

In the last few years, Balanchine has produced two spectacular choreographic achievements. The first was the hour long Bicentennial tribute Union Jack which premiered in May 1976. In the Spring of 1977 came perhaps the most lavish production in the New York City Ballet’s repertory, Vienna Waltzes, which was greeted with resounding critical and popular acclaim. Through the wonders of television, millions of people have been able to see New York City Ballet in their own homes. Choreography by Balanchine, a four part Dance in America presentation on the PBS series Great Performances, began in December 1977. Included on the programs have been The Four Temperaments, Tzigane, Prodigal Son, Allegro Brillante, segments of Jewels and Ballo della Regina, one of his more recent works. Balanchine travelled to Nashville with the company for the video tapings in 1977 and 1978 and personally supervised every shot, in some cases revising steps or angles to be compatible with the camera. The series has been broadly applauded by critics and audiences over the country and was nominated for an Emmy.

In January 1978, New York City Ballet participated in the acclaimed PBS series Live from Lincoln Center for the first time. Coppélia, choreographed by George Balanchine and Alexandra Danilova in 1974, was seen live from the stage of the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center. This presentation also netted Balanchine an Emmy nomination.

Although New York City Ballet has entered its fourth decade, the energy and achievements of George Balanchine continue unabated. Two of his most popular recent works, Ballo della Regina and Kammermusik No. 2 were premiered in 1978, and in December 1978, Balanchine, along with Marian Anderson, Fred Astaire, Richard Rodgers, and Arthur Rubinstein, was one of the five recipients of the First Kennedy Center Honors. The Awards, which were presented by President Carter in an official ceremony at the White House, were followed by a nationally televised program honoring the recipients and their achievements. The citation read in part: “Each has raised the artistic standards to which successors must aspire, but more importantly, each, by talent and dedication, has raised our hearts.”

The 1980’s promised even more in terms of both creativity and recognition. Balanchine introduced four new works to New York City Ballet audiences in the spring of 1980: Ballade, to music by Gabriel Fauré; Walpurgisnacht Ballet from Charles Gounod’s opera Faust (this ballet was created for the Paris Opera in 1975, but was restaged for the New York City Ballet); Richard Strauss’ Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, (Balanchine created this comic ballet for the New York City Opera in April, 1979, and it was first performed by the New York City Ballet in May 1980), and finally, in June 1980, Robert Schumann’s Davidsbundlertanze.

Also, in the spring of 1980, Balanchine was honored by the National Society of Arts and Letters with their Gold Medal of Merit, and by the New York Chapter of the American Heart Association with their Heart of New York Award. He was also informed that the Austrian Government would be awarding him the Austrian Cross of Honor for Science and Letters, First Class. This Award joined his French Legion of Honor, his French Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters decoration, and his 1978 Knighthood of the Order of Dannebrog, First Class, given by Queen Margrethe II of Denmark, on the list of stellar honors given by foreign Governments for his services and contributions to the artistic development of the 20th century.

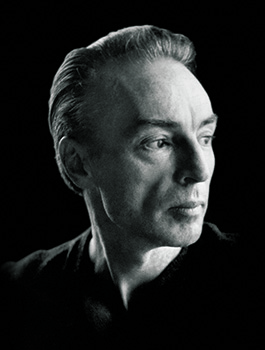

Photo: Tanaquil LeClercq.

Source: New York City Ballet